- Home

- Olivia Clare

Disasters in the First World Page 2

Disasters in the First World Read online

Page 2

“You were at the lake?”

“I can’t see to its bottom. Looking at it that long makes me never want to look at land.”

“Where’s your backpack?” he said.

“I’ll be back in a minute.”

She went to her bedroom. He almost followed her; he went to the bathroom. Her cosmetics, her face powder, her tiny bronze cylinders of perfume were on the glass countertop. A canister of rouge had spilled. He collected the grains of rouge in a mound between his fingers and then released the mound into the sink. When she was ill, he’d had to help her to the bathroom. She’d put both arms around his neck while they walked. There is no gulf between humans wider than that between the ill and the well. When she was finished, she’d call for him to help her to the bed. She’d told him she had been trying to discover something unearthly, being nearer death. She couldn’t find it. She’d told him he could have her pearls, her dog. Everything. How incredible, impossible, that she was completely well now and did not need him.

The light was off in her bedroom, but before he reached the doorway he heard her talking to herself, so softly he couldn’t make out the words. It seemed as if she was trying to calm herself. He could smell her, the lotion she used on her face: lavender, clean. She sat on the bed.

“Mother?”

“Is there soup left?” she said, when she saw him. She looked startled. “For tomorrow’s lunch?”

“What were you doing?” he said. He switched on a lamp in the room. He moved to touch her, and her shoulder tensed. He moved away.

“What?” she said.

“I saw you,” he said. “In that house. You told me you’d stop going outside.”

“I don’t think I said that.”

“I saw you go in that cabin.”

“Pétur lives there, by himself. I met him one time, walking.”

“But you agreed with me,” he said. “It isn’t healthy.”

He wanted her to say it now, to say she agreed, to apologize.

“Pétur,” she said, “has turned into a friend, I think.”

She looked past him, toward the door. She was done talking. He saw in her face she intended to dismiss him. With her, you could risk nothing. She forgave nothing, not the slightest imposition upon the complex world she believed in. She saw that he was simple, he thought, ordinary. It scared him to watch her that way. Scared him more to watch her watch him that way.

Adam slept the kind of skeletal, half-sleeping wakefulness that allowed him the belief he was asleep. A car door somewhere in the dale closed, and he glanced at the digital clock, then turned on the TV. All European flights were stranded, and cots and cotless irate passengers crowded Heathrow terminals. Eyjafjallajökull had erupted a second time, ash descended on London and Scotland, and there was concern about Katla, another volcano, in Vík í Mýrdal.

“Could you turn it off?” Laura called from her room.

She left the cabin before he rose. The tattoo of her boots on the wood floor.

He came into a sheer fog at the end of the path. It was very early. There were no lights on in the cabins, most of them probably empty.

The lake was now dusted with faint patches of ash. He hadn’t been able to convince himself not to follow her. He stopped at a boulder too tall to sit on and tightened the scarf around his face. The water, hitting the edge of the boulder, sprayed up in a small spire. The lake was the color of weathered nickel. Rocks like globules of oil littered a shallow bed at the shore. Across the lake, the other cabins were dark, too. A waterfall, tiny from where he stood, forked a few feet from the top of the fjall.

He walked the same path he’d seen her walk the day before. Bugs nagged his arms. He passed abandoned cabins; some had yards with patio furniture. In one yard was a yellow plastic toy car with ash on its roof.

He came to the bottom of the steps he’d seen her climb. Pétur’s steps. Trees obscured the house. From the bottom of the stairs, Adam could see only the housetop, the woodstove chimney.

There was a table on the porch. A small gas grill. He stepped over an open garbage bag spilled on its side. He decided, without really considering, to crouch below a screened window and to look in with one eye.

Adam could see his mother at the other end of the house. She was alone, putting pots on the stove, her lips in motion. The cabin was one room, much smaller than theirs, with hardly any furniture. A table with chairs, a bed, an armchair in the corner, no refrigerator, dark rhombuses on the wall where frames had been. He could hear her now, talking quickly. He studied the interior. She was alone.

On the floor were her green flannel coat and the backpack he’d seen the other day. Rocks she’d collected from the shore were stacked in a pyramid and placed as a centerpiece on the table. Open cans on the counter, cans he recognized from their house, cans he’d bought at a nearby town store. She was talking, and he made out not the words, but the tone, the cooing inflection.

She became very quiet. He watched from the window. She brought a bowl of dim liquid to the table and ate, closing her eyes. He watched this a long time. She put her bowl and spoon in the sink. Then she pulled her dress over her head. She had on a pale slip. She took off her rings. On the bed, she climbed on top of nothing, of no one himself, and moved her hips forward and back.

The Visigoths

I let myself in with the key. Dark cumulus carpet stains, half-eaten fast food and burn marks on the coffee table, video games and consoles, plastic eyedrop containers, cereal boxes, instant pasta. Above the TV, a poster of a long line of ectomorphic college cheerleaders. Blake’s bedroom door, decorated with scuff marks and boot-made dents, was closed.

“Come out,” I said.

He made his teachers “nervous”; he corrected them. He remembered and recited beginnings of 1950s dime store novels, batting averages of dozens of baseball teams, Latin names of spider species in Chile and Tanzania, and he knew paintings, about which he did and didn’t care. He was thirteen. Our mother, Deedee, had him entertain dinner guests—yes, sir, the etymology of error is wander. Delilah didn’t shave off Samson’s hair, her servant did. Domodossola, in Piedmont, was conquered in 12 BCE by the Romans; the Romans themselves were sacked by the Gauls, the Normans, the Visigoths, the Vandals.

“What?” I could hear him on the other side of the door, his voice still slightly high. “No.”

“Come out right now.”

“I can’t.”

“I drove out here just to see you.”

“I drove out here just to see you.” When he didn’t know what to say, he mimicked you.

“I’m serious,” I said.

“That’s right.”

“Blake. It’s okay.”

“Thank you, and have a nice day.”

“Let me see you.”

“I smell,” he said.

Deedee had called me from work, worried about Blake. He’s my half brother, fifteen years younger, born to Deedee and her second ex-husband. Blake lived with Deedee and her third husband, an oral surgeon, a consummate Dullard (what Blake and I called him). Blake opened the door in his long stained undershirt and glasses with lenses so thin they seemed not there.

He liked pornography, the Internet. He liked explosions, chase scenes, TV shoot-’em-ups and crashes, gang fights on the local news. Social networking sites, pop songs and rap, sitcom reruns in the afternoons. He hoarded gumballs, fruit sours, Sixlets, jelly beans, lollipops, Lemonheads. Weeknights he watched adult cartoons.

Deedee let him stay in the guesthouse, behind the main house. She thought this made her a good mother, progressive. There was a sheetless king-sized mattress on his bedroom floor, something chaotic and colorful on the bedroom TV. He stood, waiting for some end to come to this moment that, like most moments, was merely stalling him—he waited to return to whatever it was people like me kept him from, and I told him to shower, right now, a

nd he did.

It was summer; I was twenty-eight and recovering from the previous year. I called myself a painter but didn’t paint. Deedee gave me some money. I taught adult art classes at the community center and was compensated so little that I couldn’t have my car’s air-conditioning repaired. I apologized to Blake on the drive—he just looked out the window.

His counselor’s office specialized in teenagers, anxiety, attention deficit, autism, social anxiety, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive, the menu. In the waiting room was a generic, framed Escher spiral staircase, eighties rock on a boom box, overlaid by sound from a saucer-shaped white-noise maker in a corner. Well-browsed women’s magazines on the table.

“This really is obscene,” said Blake, gesturing to the waiting room as if showing me a museum piece. His arm was so thin and breakable—we were both smaller than average, something we’d inherited from Deedee.

“Did you know that ninety-eight percent of women are dental hygienists? Interesting? Relevant? Or who the hell cares? Your thoughts on this, please, Miranda.” He took a pamphlet from the little rack, tightly rolled it up, and held it to my mouth.

“Well, what you have to remember is that what we think of as hell is just a Judeo-Christian construction,” I said into the microphone. He seemed satisfied.

A boy sat beside us, eyes closed, dreamily stroking the inflamed rims of his nostrils. On the other side of the room, a girl was hunched over, her hands between her knees, and two other kids, with their parents, watched their phones, scrolling and tapping, in front of a sign that read cell phone use is not permitted in mental health and another that read if you see something, say something.

“That’s true about cell phones,” said Blake, taking off his glasses to clean them with his shirt.

The counselors, women and men in shabby business casual clothing, all Gen X and Baby Boomers, retrieved their patients one by one, looking apologetic, their mouths turned down, a universal expression: I’ll do what I can. These were the people who’d eroded their patients, who’d realized the mistake too late, who tried to build them up again, but without clarity—witch doctors wandering far from the ruins of Freud. Each child left the room and each time, in me, there was a little ache.

Now Blake and I were alone in the waiting room. “Let’s steal something,” he said.

I would play most games he asked me to. I took a large stack of diabetes pamphlets and put them in my purse, then took a particularly thick pamphlet on domestic violence—a man’s hands clamped around a woman’s bruised face—and sat on it. There were pamphlets on medication. Blake went up to the unattended check-in desk and slowly, slowly tore the last week of August from a calendar.

“And don’t forget to bring condoms,” he said, kneeling like a knight in front of my chair and offering me the torn week.

“Inappropriate,” I said.

“Sorry.” He smiled. “And have a nice day.”

Zoloft and Paxil and Prozac. Cymbalta and Klonopin. SSRI. This is the language of friends of mine from college. Daily pills to save them from defeat. Kate’s grandfather died. Leigh had a miscarriage, a sister in a car crash. Johannes simply had bad dreams. I once told him I disliked my own bad dreams but didn’t wish them gone. I could watch myself living all the parts of my life—ecstatic, painful—and I wanted all parts, all threads, even the unraveled.

Blake’s counselor arrived, younger than the others, her facial features so delicate she seemed a child herself. When they left for her office, I pumped sanitizer onto my hands from a bottle on the table and rubbed. He sent me a text message from inside: “Such a rebel! Using my cell phone in the mental health!”

“Me too!” I replied.

After a while, the counselor came to take me to him.

“I’m Kerry,” she said, closing the office door and sitting at her desk. “You can sit right there.” Her voice made me think she was my age or younger.

Blake sat next to her and faced me, too, across the desk. I wondered if he enjoyed the attention from his doctors. He’d once told me: “You really have to give them a show, that’s what they’re here for.”

Another saucer-shaped white-noise maker in the corner. Neutral carpet, fluorescent lighting, framed pastel floral prints. One of Kerry’s eyes was red, with what could have been the beginning of a welt underneath. Maybe a husband or boyfriend had hurt her, had put his hands around her head. She seemed fragile, wistful. Maybe I could help her.

“He needs to set an alarm and take his medication in the morning,” Kerry said. “If he takes it at night, he won’t sleep.”

“He could try a different serotonin reuptake inhibitor,” I said. “Why hasn’t anyone suggested that?”

Blake shuffled two appointment cards in his hands rhythmically.

“I don’t know too much about the different chemicals,” Kerry laughed. “That’s for the doctor.”

“The only way to deal with an unfree world,” said Blake, “is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.”

“Hm,” said Kerry.

“I didn’t say that, by the way. That’s Camel Camus.”

“You don’t know anything about chemicals?” I said.

“The psychiatrist decides that,” she said. “As well as the dosage. She’s across the hall. But it’s important that he sets an alarm to take his medicine.”

“He’s thirteen, and it’s summer,” I said. “That doesn’t seem realistic.”

“It is what it is.”

I wanted to believe the solution to the problem was in that tautology, and so I stood. We would attempt to leave with the particular relief that comes after a doctor reassures us the problem is common, treatable, and will, certainly, be gone soon.

“Let me know if anything else comes up,” said Kerry, looking at Blake. “Have a good one.”

I took him out to an early dinner and told him he should call Deedee. He preferred not, he said. I asked about school in the fall, if he was ready for high school, I asked about girls, if he’d seen his friends lately, if he thought the salad was soggy, if he was too hot or cold, if he wanted ice in his drink, and he answered it all, monosyllabically, waiting for this, too, to be over, staring past my shoulder, watching a basketball game on TV on the restaurant wall.

On the ride back to his house, I said, “How are you feeling?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“I think you do.”

“That’s right.”

“So. Tell me.”

“Have a good one,” he said.

I didn’t hear from Deedee or Blake for two days. I tried calling, once very late and another time early. On the third day, Deedee called.

“He really needs you. He’s been asking about you.”

“Is that true?” I said.

It’s trite to say it: I didn’t think she was proud of me. I wasn’t properly pursuing my painting. Though I lied to her about it, she knew nothing was moving forward there. When she was a child she’d worked a little as an actress and a model, in a toothpaste commercial and some clothing catalogs. Then she’d danced, ballet, but was told that she wasn’t good enough to continue professionally. I felt her sensing that failure in me, a lack of talent or will. Maybe she started her family early to forget dancing. At twenty came her first husband, my father, now long forgotten by her, hardly mentioned.

“Blake misses you,” she said. “I’m at work, and he needs to be around people.”

“What happened to his friends?”

“He doesn’t tell me very much, you know I don’t know. It’s just how he is. But you need to go get him and take him somewhere. Maybe the mall. Only don’t tell him you’re taking him to the mall, or he won’t go.”

“The problem is he has no impulse control,” I said.

Deedee used to tell me that about myself. And other things. When

I was a kid, she would look for symptoms of mental illness in me—washing my hands more than I should, not eating enough, worrying excessively.

“You saying that right now doesn’t help anyone,” she said.

A few years ago she’d become half-aware that I had come to disrespect her, that I treated very little of what she said seriously. I’d married Victor in part because the gravity of marriage, the ritual and contract, might have distanced me from her. Of course it didn’t work, and our marriage didn’t, either.

I sent Blake a message on his phone: “Coming to get you. Be ready. 15 minutes.”

He wrote back incongruously: “Hey qtpie.”

I bought him a pizza in the mall. We ate in front of the spinning cake-like carousel, with kids on repeating horses. I took him to three clothing stores. He came out of the dressing room, the clothes too large, sleeves drooping, as if asking me not to judge him for what he was, because none of this was what he actually meant. None of it. I wanted to tell him I already knew. He combed his blond-white hair sideways like an old man, to cover a red, scabbed-over bald spot. He’d been born with it—one of those tolerable imperfections that means little at first. A salesperson suggested we try a children’s store. Nothing fit.

“You shouldn’t insult customers,” he told me when we’d left. “Customers pay your taxes! Imbeciles.” He shook one fist above his head, the gesture of a cartoon villain.

I took him to a pet store. The dogs that were awake looked at us with wet, winky eyes, like beached whales barely alive. I looked back sleepily. Blake leaned on a shelf and stared. I entertained an image of us all living underwater.

“That’s Leslie,” said Blake, straightening his glasses. He was watching a tall, indifferent girl with crimped hair dyed lavender. She faced us and stood in front of a cage of gerbils on wheels.

“You know her from school?”

“Sort of.”

“You should talk to her.”

Without arguing, he did. I watched him say hello, then they stared at the cage as if at a television, saying things I couldn’t hear. I walked over. She slouched, hands in pockets. I could tell she was polite, that she didn’t want to be standing next to him. She seemed to be his age.

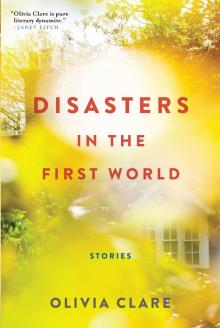

Disasters in the First World

Disasters in the First World