- Home

- Olivia Clare

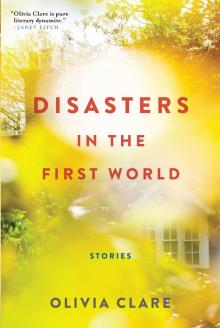

Disasters in the First World

Disasters in the First World Read online

Black Cat

New York

Copyright © 2017 by Olivia Clare

Cover Design by Patti Ratchford

Cover photograph © Yoshinori Mizutani

“Pétur” originally appeared in Ecotone, 2012, and 2014 O. Henry Prize Stories

“The Visigoths” originally appeared in Boston Review, 2016

“Quiet! Quiet!” originally appeared in Yale Review, 2014

“Creatinine” originally appeared in The Southern Review, 2014

“Two Cats, the Chickens, and Trees” originally appeared in ZYZZYVA, 2015

“Things That Aren’t the World” originally appeared in Epoch, 2014

“Rusalka’s Long Legs” originally appeared in Kenyon Review Online, 2013

“Santa Lucia” originally appeared online in n+1, 2013

“Little Moon” originally appeared online (as “Satanás”) in Granta, 2014

Excerpts from “Theater” and “Douve Speaks” from EARLY POEMS 1947–1959 by Yves Bonnefoy, English translation copyright © 1991 by Galway Kinnell. This material is used by permission of Ohio University Press, www.ohioswallow.com.

Excerpts from “Trying to Have Something Left Over” from THE GREAT FIRES: POEMS, 1982–1992 by Jack Gilbert, copyright © 1994 by Jack Gilbert. Adapted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or [email protected].

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic paperback edition: June 2017

FIRST EDITION

ISBN 978-0-8021-2661-0

eISBN 978-0-8021-8957-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

Black Cat

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Lula Clark

Contents

Pétur

The Visigoths

Olivia

Quiet! Quiet!

Creatinine

Two Cats, the Chickens, and Trees

Things That Aren’t the World

Pittsburgh in Copenhagen

Rusalka’s Long Legs

For Strangers

Santa Lucia

Little Moon

Eye of Water

Acknowledgments

Pétur

Ash fell from the wind. She began to take long walks. Before breakfast, after lunch, she walked the weed-pocked path to the lake. White ash turned the lake’s surface to desert and the tops of fjalls invisible.

By the third morning, ash from Eyjafjallajökull coated the porch, the porch rail, the seats of the porch chairs, and the rented station wagon. The hrossagaukur had flown off, and the cabin’s weather vane creak had stopped. Laura told Adam, again, she was going out. He was her son. She tied a gauze scarf around her nose and mouth.

“I look like a robber,” she said.

“No one will see you.”

He opened the door for her into the otherworldly weather. She was garish in the ash in her green flannel coat. At the cabin window, he watched her diminish, and like a little boric flame a quarter mile away, her back rose on the path, then shrank and went out.

This dale in Iceland had a permanent population of eighty-six. They had seen almost no one—once or twice, before late sunset at nine o’clock, they’d heard shouting children. Icebabies, Laura called them. You can’t ever see them, of course. They’re made only of sound.

Adam was a data systems analyst. He was thirty-six. He lived in a one-bedroom apartment in Palo Alto. It was tiny and out of the way, on the other side of town from Laura’s house, which she’d once shared with his father. Iceland for two weeks had been her idea for her birthday. She’d just turned sixty-one, and she told Adam she didn’t believe it, and he shouldn’t, either. She’d said, You look in the mirror and acknowledge you’re as old as you like. She felt nineteen, mostly. She looked fifty.

She returned from her walk late enough that Adam had made soup. The cabin had five rooms, floors of dull old wood, a kitchen and dining area adjoining the living room. There was a woodstove, a coffee table with a fan of women’s fashion magazines, an expensive guitar on its stand, a box of black rocks and cockles from the lake, a striped sofa, a ripped cushion. They were renting the cabin from a family who’d advertised the place online.

“On the news they’re saying don’t go out at all,” he said.

“But no one’s said anything like that to me.” She lowered her scarf from her face to her neck.

Bits of ash stuck to the silvering blonde roots of her hair. She was tall, too slim. She wore blue jeans and boots.

“On TV, Mother.” He put a roll and a bowl in front of her, soup with halibut and celery from the store in town. She was still shaking from the cold.

“Well, people are out there,” she said. “I talked to some people.”

“Who’s out there? Rangers?”

“I think it’s coming down most at the lake,” she said. “Right now it’s like the moon. It’s not dangerous on the moon.” She untied the scarf and put it on the dining room table. “Come with me, come to the lake.”

“It’s unhealthy.”

She picked up a chunk of fish in her spoon. “What does antimatter mean?”

“What?”

“What’s antimatter?”

“Antimatter?” Adam wiped his mouth with his napkin. “Sure, it’s like a mirror image, a negative image of matter, like matter’s twin. And there are antiprotons. Antielectrons—”

“What happened to all the fish?” she said.

“In the lake? All dead, from the ash.”

“I don’t think they feel anything.”

She walked in, waking Adam from a nap in a chair beside the fire in the woodstove. Her scarf was tangled around her neck. Her green coat off, a rip in her shirt at the elbow. She held her arm to her chest: a bright red cut like a seam showed through the rip. She went into the bathroom with a sleepwalker’s involuntary smile and an alien tannic scent, maybe wine.

“You’re going to laugh,” she shouted, “when I tell you what happened.”

“Let me help you,” he said, getting up from the chair.

“It’s fine,” she said. “Sit down. It doesn’t hurt.”

Maybe she’d stolen a neighbor’s skiff, as she had the week before, the day they had argued because he looked out the window and said a fjall was beautiful. She’d told him not to call things that, told him that one word, beautiful, a word his father had used constantly, was limiting. She had learned the l

andscape, the words rill, caldera, and the names of wildflowers. Nights after her afternoon walks, she would sit with a field guide. I have a bird heart, she’d say, your mother, the bird. Precise knowledge of a fjall’s origins, or of the call each bird made, was the closest she felt to wisdom, because land, because details, she said, were important. They were solid and finite and felt infinite.

“Let me help you,” Adam said again. “Please.”

She came back into the room. “I was climbing up that boulder on the shore. I had my camera with me and a bird swooped near my head, and I tumbled off. Your mother. On the ground.”

“No more walks.”

“I wasn’t going to,” she said.

“It’s like with those eggs in California. You had that accident when you reached for the nest. You forget what you’re doing.”

She looked at him, expecting a response. What did she want? He knew how she thought of him, his normalcy. She said what she thought, and there was both innocence and maturity in that. When she was eleven, she’d told him, she had watched her brother die from a rare leukemia. She spent the rest of her life trying to strike lightning back.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “The eggs were fine. They were alive.”

“I believe you,” he said.

Laura had raised him on her “wisdom and whims”—she had taken him to museums and operas, he’d had a violin and no television, she’d taught him the names of native ferns and trees around their house. Sometimes she had invented names. On Adam’s first day of high school, she’d taken his face in her hand and told him school was for wolves and sheep, that wolves and sheep ought to be separate, and that she wanted him to be a wolf. She was a wolf. His father was a sheep.

He’d attended college in Connecticut, joined a fraternity, been an average student. He visited her that first Christmas, then stopped. He stayed on after school and got a job in Bridgeport. When they talked on the phone, she told him he’d become something else, someone she didn’t understand.

Four years after he graduated, Laura called him: they’d found a small tumor in her neck. He flew to Palo Alto to live with her awhile. She’d said it wasn’t necessary. He had rented a small apartment and got a job there, told himself he’d been planning to live in California eventually and that it was the right thing to do. She recovered fully, incredibly. Now he saw her for every Sunday dinner, some weeks more frequently to help around the house, though she claimed she didn’t need him.

He aged uneventfully. Gained a little weight, lost a little hair. He was often ill with some nonthreatening flu or infection; he had problems with his joints. He saw several doctors and specialists. Sometimes he had a girlfriend, and there was a coworker he slept with occasionally.

But Laura—she’d become younger, uncommonly healthy. Woke earlier, stayed up later, ate what she wanted, was always hungry. It was as if she was subtracting years. Some days she told him her ecstatic dreams, which never contained people.

After dinner she stood on the sofa and took down the three framed watercolors on the living room walls.

“Be careful,” he said.

“It’s just that they’re a bit disgusting. Kitsch.” She balanced on the back of the sofa, her feet clinging to the edge. She’d painted her toenails pink the night before. “I should have done this the day we got here.”

“They’re not ours.”

“I refuse to stare at them anymore. It’s unhealthy.” She jumped off the sofa without trouble and stacked the watercolors in a corner and looked around the room for anything else that offended her. She took the fashion magazines from the coffee table and put them in a drawer.

“I think I’ll go for a walk,” she said.

“Please don’t.”

“Please don’t tell me don’t.”

“Mother. Don’t go outside.”`

“You love scolding me. You think you get something from it. Like your father.”

“All right,” he said. “Then I’ll come with you.”

They walked to the lake with scarves tied around their faces—he’d insisted, though the ash had stopped falling. Anyway, it was cold, he said. It was mid-April. He could hardly see the other cabins, spaced around the dale, in the northern pre-twilight. Another constellation of cabins, mirroring their own, was across the lake. A giant fjall above them.

She had been asking to come to Iceland for years, ever since she’d met an Icelandic man, divorced and in his fifties. After she’d recovered from her illness, she had started seeing him, and then had stopped abruptly. But she still needed to visit the place that felt like both “the end of this world and the beginning of another,” as the man had told her. Adam wouldn’t let her travel by herself. What a good son you are, they’d said to him at work. Your mother’s very lucky. He’d felt he had no choice.

He was quiet while they walked, he knew that was important to her, but he wanted to say something about the red blinking light across the lake—the rangers’ station—and the sound of the skiffs knocking against one another, tied on the shore. He felt practical. He felt he wasn’t there.

“God,” he said finally.

“What?”

“Everything. We’re trapped. A volcano erupted, we’re trapped.”

“We have a car,” she said.

“It needs gas. It’s a hundred dollars here for a tank, you know. A hundred twenty-five.”

“I see.”

She didn’t. The trip had cost him thousands. She owned her house in California outright, had a small pension from Adam’s father, and Adam took care of the rest. She knew nothing of money; she’d forget to pay bills. She’d bought a car she couldn’t afford. Here, of course, but even in California, she acted as though currency were foreign to her. At restaurants, she treated money as if it were only paper, holding it by the corners. She left waiters incredible tips.

“We’re not trapped,” she said.

“We are,” he said. “That’s the perfect word for what we are.”

“Think of this as something else, meaningful. Maybe this is a land of ash now. This is some kind of other place. Ashland.”

She was asking him to concede, to play her game, as she’d asked him to imagine things when he was a child. He wouldn’t anymore. He said nothing, and she looked at him with disappointment, as if he had played the wrong notes on the piano. But in fact he’d played nothing.

They’d come to the lake, a layer of ash on the surface, gray-white. Torn bits of paper. She took off one of her shoes and put a toe in the shallow water. Specks of ash stuck to her pink toenails. She let her whole foot sink in.

“Isn’t it too cold?” he said.

“We’re not trapped,” she said.

“We’re trapped in a volcano. It’s remarkable.”

“It isn’t remarkable. Nothing is merely remarkable. You think something can be one word,” she said, taking off her other shoe and standing with both feet in the lake. “You can enjoy yourself. Not think the way you do. You’re not always just who you think you are.”

She spoke softly, as if to herself. Her inflections were neutral, anonymous, any evidence of her midwestern origins gone. She had sung with a band in the seventies in Ohio, she often told him. Music producers had been interested, but her own mother had been jealous of any success, of any attention she’d received.

“Look, I’m tired,” he said.

“Everyone I know is always tired.”

“I’m sorry,” he said.

She looked at him—a stranger’s doubt and maternal empathy—and he wanted to ask her to either hug him, as sentimental as it was, or leave him alone. An act of kindness, or nothing at all.

“Your father said it that way. You never heard him say it.”

“We should walk back now,” he said.

In the morning Adam drove to the base of the dale with his laptop on his thighs,

bumping against the steering wheel. The wagon’s tires crushed sprigs of lupine powdered with days-old ash. Parked across from the ranger station, he leeched its Internet and e-mailed clients. They were scheduled to return to Palo Alto in two days, but he knew they couldn’t leave by then. The road to Reykjavík was closed indefinitely.

He had been gone a half hour and was driving back, when, rounding a switchback, he saw Laura two hundred feet below, a little green coat in high boots. She used a bowed branch as a walking stick. She carried a backpack he’d never seen.

He parked the car on the side of the road, tied his scarf around his face, and followed her down the path to the lake, through the tangle of bushes. She hadn’t seen him, he was sure of it, but she walked as if pursued.

At the lake he hid behind a boulder. She crouched amid drifts of ash on the black rock shore. Hands quick as a sharp’s dealing cards, she seemed to sort rocks into two stacks, then scooped a stack into her backpack and kicked the other into the lake. She was talking to herself—he’d caught her doing this before, at the cabin, washing her hands at the sink, gesturing to herself with the water running, talking and singing to no one, without words, cooing. Sometimes he thought she was too forgetful and scattered, too unpredictable. He worried he couldn’t help her.

She left the lake. He followed her down another path, overgrown with wildflowers and weeds. She was walking up a stairway to a cabin. Weather-battered, smaller than theirs, with blue shutters. No antenna on the roof, no car in the gravel driveway lined with bushes. She knocked once, then opened the door herself, leaving stick and backpack on the porch.

Adam was heating soup when she returned, holding her scarf. She had the same preoccupied, sleepwalker’s smirk, her blue jeans stained black at the cuffs. An inanimate vacancy in her eyes, wide-set as an elf owl’s.

“What happened?” he said.

“I looked for fish, for anything living. There weren’t any eggs out there, either.”

She had been gone a few hours since he’d seen her enter the other cabin. Her backpack was gone. She put her scarf on the table and warmed her hands in the steam from his teacup.

Disasters in the First World

Disasters in the First World